Developing Countries Face Debt Crisis: A Call for Concerted International Action

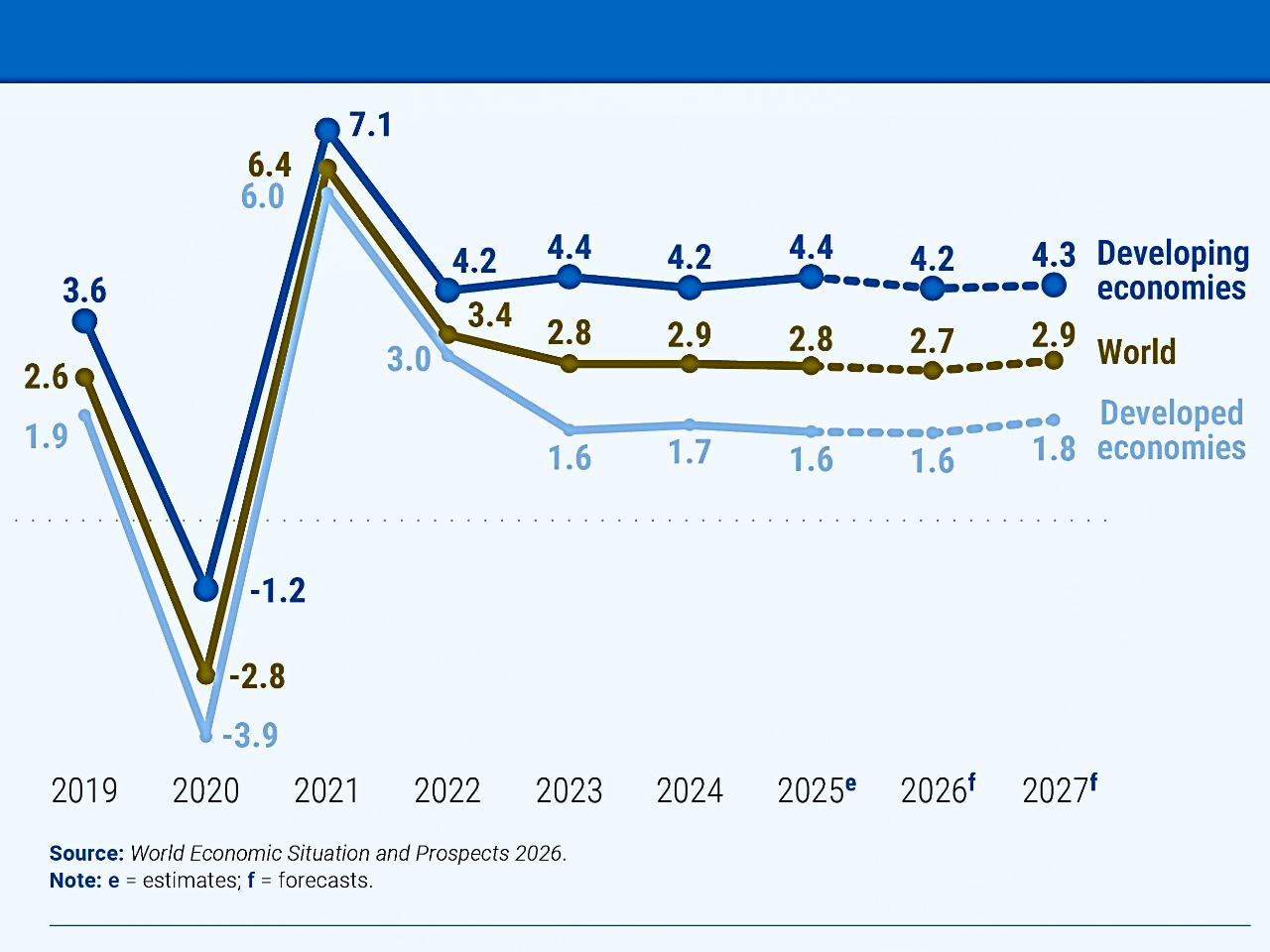

The developing countries went into 2025 with a heavy burden on their economies occasioned by a conglomeration of global and local challenges. Significant changes in the international policy, increasing geopolitical tensions, a tightening of international financial resources, and a severe decrease in the official development assistance (ODA) have all played to the disadvantage of export performance, reduced fiscal space, and lowered growth opportunities. These pressures have played a major role in eroding the sustainability of debts and diminishing the capacity of governments to invest in sustainable development priorities. Even though the rate at which external debts were accumulated decreased in 2024, this reduction was not reflected in the financial resilience. Rather, fiscal and external buffers persistently declined in a majority of the developing economies, subjecting the economies to more vulnerable debt and macroeconomic instabilities.

In 2024, the level of total external debt in the developing countries grew by 2.6 percent and reached USD 11.7 trillion. Although this was a low growth rate compared to the past years, the cost of servicing this debt was very high. Third-world nations had to service USD 1.6 trillion worth of foreign debt, and this committed the limited state resources to alternative priorities, including education, healthcare, infrastructure, climate change mitigation, and social support. This debt servicing pressure is both the volume of debt that has not been settled and its nature. The increase in interest rates, a reduced maturity period, increased commercial borrowing, and foreign currency exposure increased the cost of debt servicing even in cases where the overall debt stocks seem stable.

The sustainability of debt deteriorated in most of the developing countries in 2024, despite an apparent limited change in the headline debt indicators. Except for China, the global South public and publicly guaranteed (PPG) external debt service has increased to 8.4 percent of government revenue, approximately one-fifth higher than that of 2023. This kind of increased growth is a pointer towards increased financial strain and reduced financial ability. Similarly, the ratio of total debt service to export was 16.3 percent. The growth was by high-income countries, although it fell a step higher than in 2023. In comparison, debt sustainability deteriorated in a major way in low-income and lower-middle-income countries, covering the underlying weaknesses. The countries most affected were the low-income countries. A decrease in economic development, declining commodity prices, and declining export payments led to a nearly doubled debt service payment in 2024. These countries employed the highest amount of 24.2 percent of the foreign debt service on export earnings and 18.1 percent of government revenue on PPG debt service.

The levels are broadly unsustainable, and they directly jeopardize the process of achieving poverty reduction and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The developing debt situations were also getting worse in the lower-middle-income countries, especially with a so-called wall of principal repayments coming due in 2024. This refinancing pressure augmented rollover risks, and these economies were exposed to volatile global capital markets. LDCs were further worsening their debt sustainability. Conflicts, geopolitical tensions, slowdown of growth, and falling government revenues exacerbated fiscal stress. By 2024, LDCs spent 22.3 percent of their government income on the debt service of PPP debts, the largest of all types of developing countries, and 21 percent of their exports on the debt service of total external debt. Small island developing states (SIDS) recorded some slight improvements following the great debt shock that had taken place following the COVID-19 pandemic. The increase in the economy, combined with a recovery in tourism, has been used to bring external debt service to 19 percent of export earnings and PPG debt service to 17.6 percent of government revenue. Nevertheless, the amount of debt is critically high, placing such economies in a vulnerable position of responding to climate shocks and external shocks. The sustainability of public sector external debt declined in 2024, and Sub-Saharan Africa declined the most. The amount of 18.7 percent of revenues spent on servicing the external PPG debt by governments in the region is three times higher than that of 2014. The total debt service to exports ratio has more than doubled in the last ten years, and this signifies a structural debt crisis and not a shock.

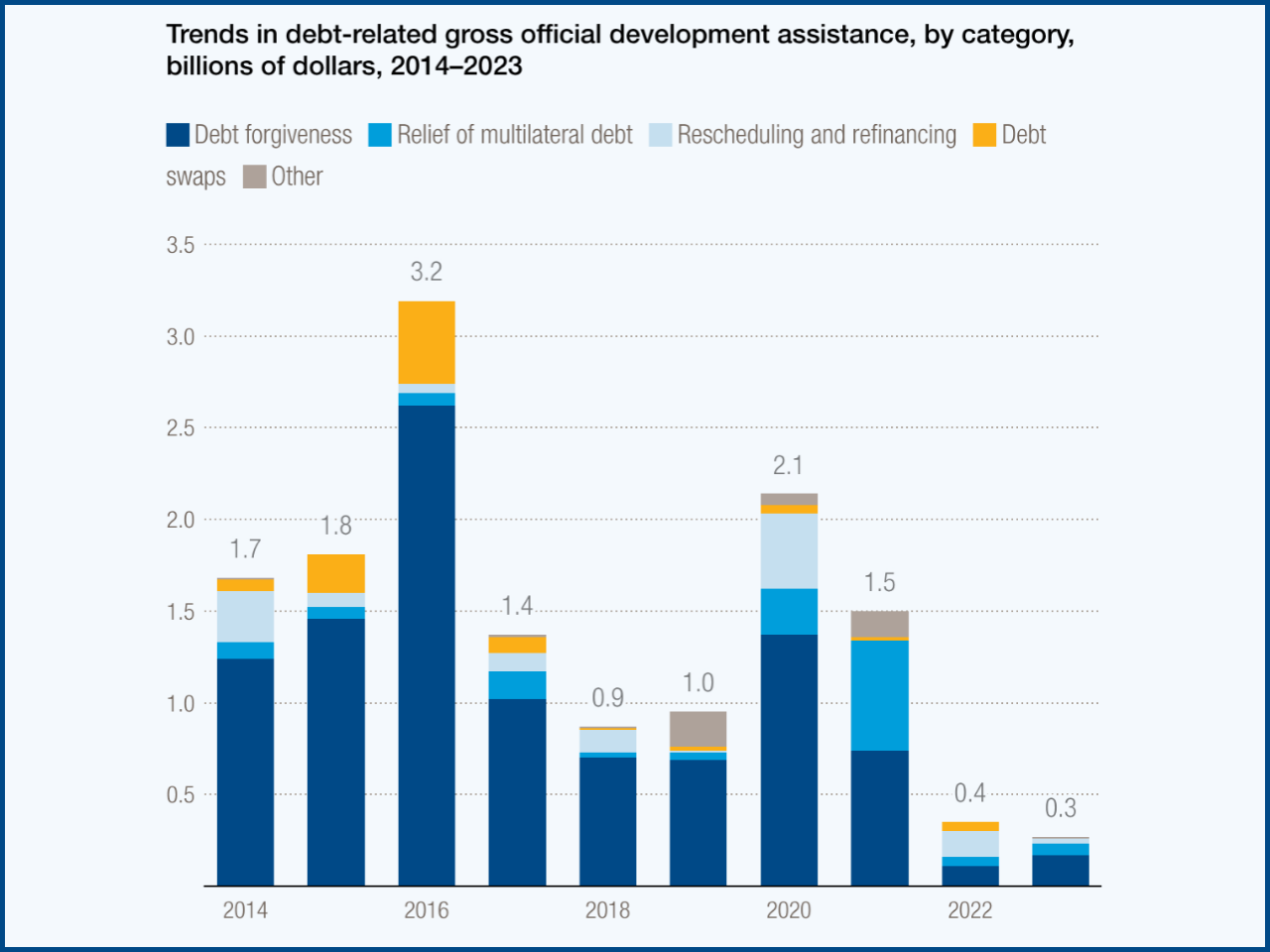

The debt crisis has increased with a drastic reduction in the official development assistance. In 2024, 7.3 percent less ODA was made by the member countries of the Development Assistance Committee (DAC), compared to that made in 2023. The aid was reduced to 0.3 percent of the gross national income of the donor countries, which is lower than the agreed international figure of 0.7 percent. ODA has debt-related components that hit an all-time low of USD 270 million in 2023, but which had temporarily increased in 2020-2021 as part of the G20 Debt Service Suspension Initiative. Debt writ-off, restructuring, rescheduling, and refinancing assistance is also reduced substantially, and bilateral debt-for-development swaps are virtually extinct. This reduction in the concessional funding will lead to the other developing countries sinking deeper into a debt and development crisis.

UN Trade and Development (UNCTAD) can be regarded as one of the key players in assisting developing states in terms of policy-driven research and consensus-building, as well as technical support. One of the pillars of such effort is the Debt Management and Financial Analysis System (DMFAS) Programme, which assists the countries in enhancing their ability to record, monitor, and adequately manage the public debt. To deal with the rising complexity of debt, UNCTAD has initiated DMFAS 7, a new generation debt management platform that provides more integrated and comprehensive solutions. The programme is presently serving 63 countries to facilitate transparency, fiscal sustainability, and good governance. UNCTAD also helps in larger UN-managed initiatives such as the Pact for the Future (2024), the Expert Group on Debt led by the Secretary-General of the United Nations, and the Fourth Global Conference on Financing Development, the outcome of which, the Seville Commitment, identifies the directions of improved development finance in the world. According to UNCTAD, the process of creating sustainable development needs to focus on cost and the composition of debt. This entails decreasing the unsustainable stocks of debts, where need be, and the mobilization of long-term, affordable, and stable financing. UNCTAD recommends, at the multilateral level, the escalation of affordable financing of multilateral and regional development banks, the enhancement of the universal financial safety net, the reformation of the G20 Common Framework, and the redesign of development-need debt sustainability analysis. It is also suggested that the establishment of a platform for borrowers will promote coordination and increase the voice of debtor countries.

On a country basis, the prescription is to strengthen the debt management offices, create investment pipelines, enhance access to foreign currency hedging mechanisms, and create platforms for debt-for-development swaps. At the national level, governments are urged to widen the quality of their investment projects, minimize the cost of debt-swaps transactions, extend their debt maturities, lower borrowing costs, improve their communication with their investors and credit rating agencies, and diversify their sources of financing by involving non-traditional bilateral sources. The analysis of UNCTAD 2025 highlights that the structural debt and development crisis in developing countries is the issue, but not a liquidity crisis in the short run. Devoid of concerted international reforms, greater concessional finance, and development attuned debt plans, debt servicing will keep blocking crucial investments. Debt sustainability and sustainable development have to be sought jointly through a systemic, multilevel response.

ADVERTISEMENT

Free To Activate Membership