Debt Transparency: A Crucial Step Towards Sustainable Development Finance

Debt transparency is essential for the assurance and monitoring of debt sustainability. In recent years, some borrowing countries have obtained full access to markets with credible creditworthiness, only to later reveal hidden debts, leading to deep economic crises. Judgments about debt sustainability can only be made with timely and comprehensive reporting of debts and transactions. Most sovereign borrowers are facing rising interest rates, high refinancing demands, and constrained access to the market to finance their debts and are turning to off-budget or non-traditional financing methods, such as private placements, loans from the central bank through swaps, collateralized loans, and over-collateralized repurchase agreements. These instruments are frequently opaque and consist of complicated legal and operational arrangements. In low-income countries with limited institutional capacity, the governments may not even know all their financial exposures. This complexity will diminish the development finance agenda and increase the risk of insolvency. Transparency helps investors in the sovereign debt ecosystem.

We have seen progress made since the World Bank’s 2021 thorough public debt transparency assessment was found. More borrowing states are now producing debt information that covers broader areas and more quickly. The World Bank’s Sustainable Development Finance Policy (SDFP) and other such initiatives have provided incentives to disclose more, while other organizations, including the World Bank and IMF, have provided technical assistance to bolster debt reporting and recording systems. On the creditor side, G7 countries have started publishing the particulars of their lending portfolios, further supported by the G7’s debt reconciliation process with the World Bank. This ought to be expanded to include all of the G20. A recent example of Indonesia’s debt reconciliation with the World Bank is positive. Moreover, the World Bank is working to expand its Debtor Reporting System to include more complex debt instruments and the quality of the data. Which academic institutions and think tanks have created databases of lending terms and contracts to enhance transparency? Increased openness in debt restructuring processes is just as important. Organizations, including the Global Sovereign Debt Roundtable (GSDR), the G20, and the Paris Club, have advanced transparency in the G20 Common Framework by posting factsheets as well as status reports. However, many nations with unmanageable debt loads switched to bilateral exchanges, frequently behind closed doors, with specific creditors even outside of the G20 Common Framework. In the G20, gaps in transparency demonstrate the necessity for shared rules and information. While reporting on debt to creditors has progressed in low-income countries, significant gaps remain. The World Bank noted in 2021 that 40% of low-income countries had not reported any debt data in the past two years. This number has gone to under 25% now, nearly all from fragile and conflict-affected countries. However, there are still a number of major issues. For example, four out of five countries do not report loan-level data for newly contracted debt. Comprehensive sectoral reporting is rare, and reporting of borrowings at the subnational level, liabilities contingent on future events, and debts owed by public enterprises is often absent from official reporting.

As financing mechanisms proliferate and evolve and reported borrowing levels shift, there is additional risk of undisclosed debt, contingently contracted. In many instances, the governments themselves lack complete knowledge of their liabilities because of limited institutional capacity. Low-income nations have been using opaque financing methods, including central bank swaps and collateralized loans, more frequently since 2021. The government’s ability to manage the current debt portfolio is made more difficult by these opaque methods, which are frequently designed with non-standard terms, few refinancing choices, and contracts that prioritize creditor recovery. Limited institutional and legal frameworks in the nations where this is applicable are another barrier to transparency. Many nations lack legislation requiring complete debt disclosure, audit procedures, or legislative monitoring. Covenants, liabilities, and collateral are frequently not required to be published under debt management frameworks, and they are not even intended to comply with international reporting standards. Debt management offices often experience issues such as fragmentation, weak mandates, or limitations in attracting qualified staff, leading to knowledge gaps and the possibility of misreporting. The effects of such weaknesses were seen in Senegal, where the absence of legal frameworks and oversight led to a major case of reported government misreporting of debt. Even though officials are currently attempting to resolve the problem, it emphasizes the necessity of enhanced governance systems. In the last few years, a lot of debt resolutions have happened without the help of coordinated creditor committees. For better credibility and efficacy, more information disclosure guidelines might be developed for even formal procedures like the G20 Common Framework.

While there has been some improvement in the areas of openness, not all of the gaps have been filled by creditor-side initiatives and international financial institutions (IFIs). Since 2018, the World Bank’s International Debt Statistics (IDS) initiative reported on an additional US$631 billion in stated loan commitments that had not been reported previously, although the amount of loan commitments is almost equal between official and private creditors. Indirect reporting through IFIs, credit rating agencies, or other intermediaries has also contributed to expanding the debt coverage but resulted in limited and varying classifications and standards, which impede comparability across countries. The situation is better on the creditor side, where the G7 are publishing loan-level data, but several significant non-G7 creditors still do not release lending information on their sovereign loans. Although there has not been much progress on disclosing information on private creditors, less than 15 recorded loans from two commercial banks were posted on the OECD’s transparency platform before the project was discontinued. Nonetheless, G7 and Paris Club members are working towards coordinating reconciliation studies among borrowers and creditors, which ultimately can improve the accuracy of data. Expanding reconciliation studies to G20 members is a priority. Although the reconciliation process takes time, it improves the confidence in quality data and reduces the risk of debt. The process can be automated, thereby increasing the efficiency of the data and lowering costs. Due to its importance for global debt governance, debt transparency requires a complete reset. Current instances of undisclosed debt highlight the continuous difficulties in increasing debt figures and providing accurate and timely reporting. The government must report debt in a thorough, accurate, and timely manner; all creditors must follow transparent financing procedures; and radical transparency must be achieved. Strong international data sharing platforms, more stringent creditor monitoring and contract protections, and legally enforceable national debt monitoring and disclosure frameworks. Transparency changes must involve both debtors and creditors, and international mechanisms to enforce uniformity and compliance must be established. In the end, establishing the standard for debt transparency globally will boost finance for sustainable development, lower risks, and foster market confidence. The study argues the case that in order to bridge the transparency gap and build a more robust international debt architecture, borrowers, creditors, and IFIs must undertake medium-term initiatives and high-priority reforms.

Latest Explained

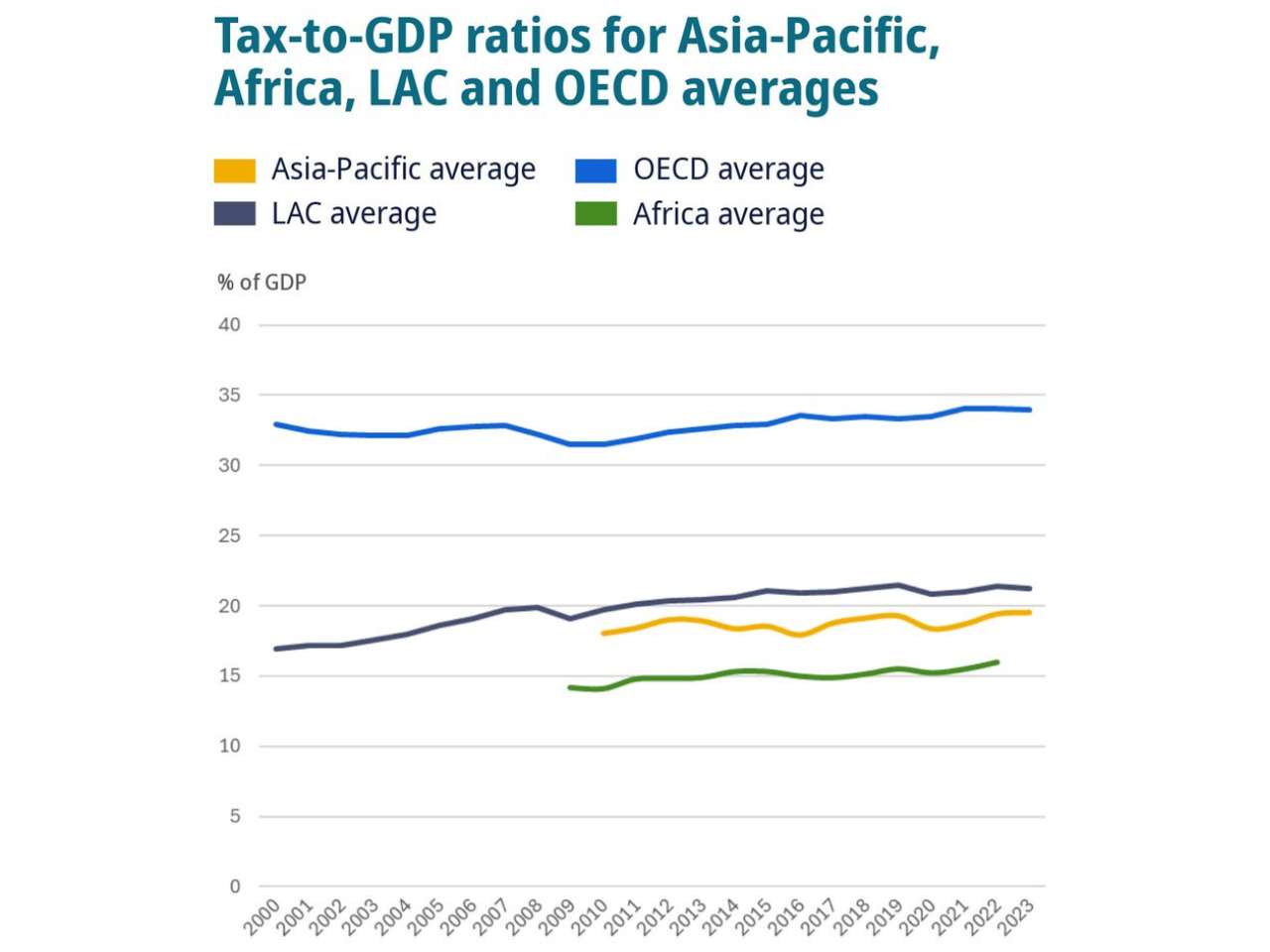

Asia-Pacific Tax Trends: Revenue Statistics 2025 Reveals Insights into Public Finances

Over the long term, or between 2010 and 2023, tax-to-GDP ratios increased in 22 economies and reduced in 15 others. The Maldives, Niue, Nauru, Japan, Cambodia, and Korea saw some of the largest improvements. Some of the increases can be attributed to tax reforms and recoveries from economic crises in Japan and Korea. In the long term, the greatest decreases occurred in Timor-Leste, Kazakhstan, China, the Marshall Islands, and Vietnam; this was due to a sudden decline in global commodity prices, which reduced fiscal revenue in these commodity-dependent economies

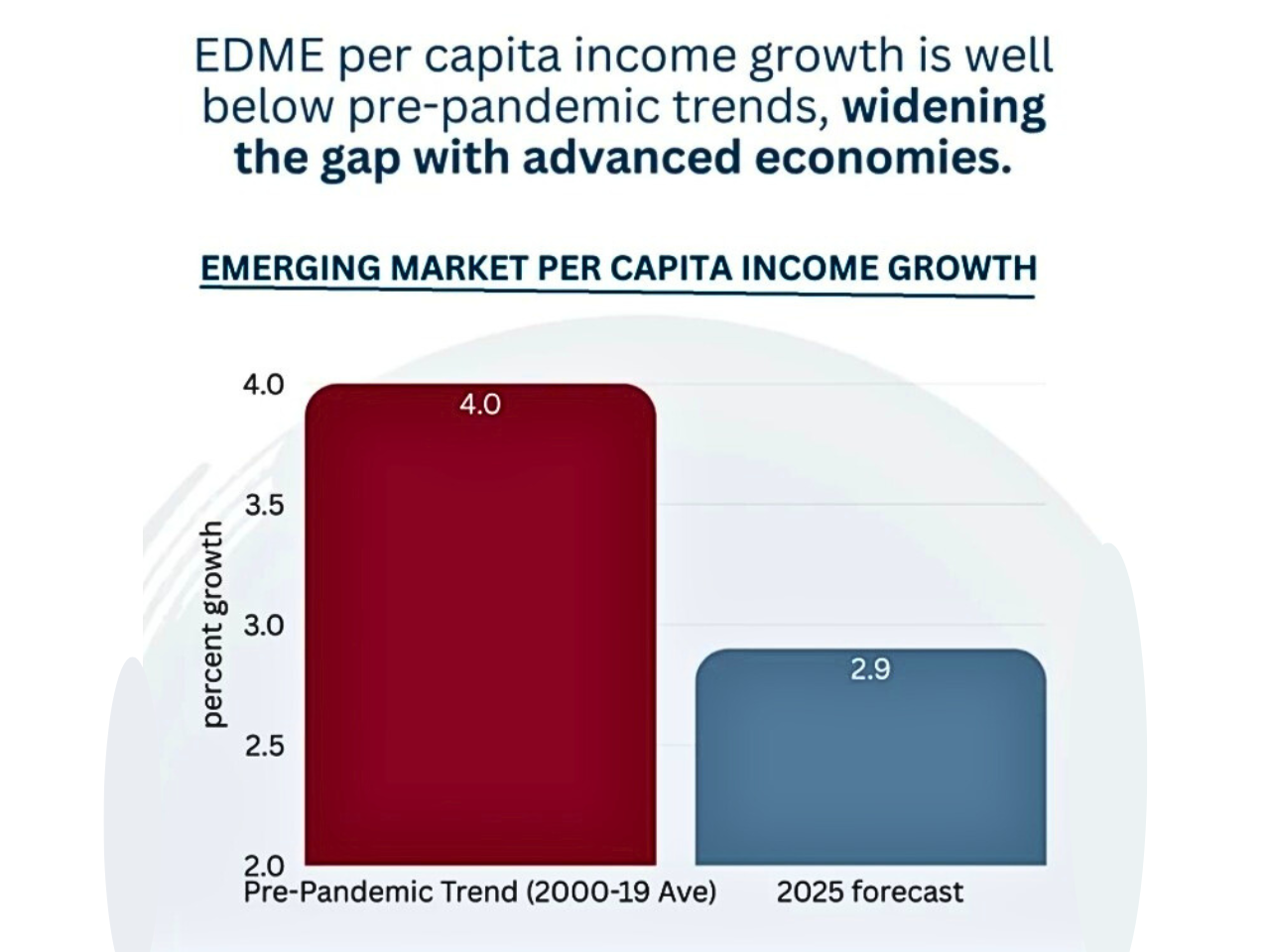

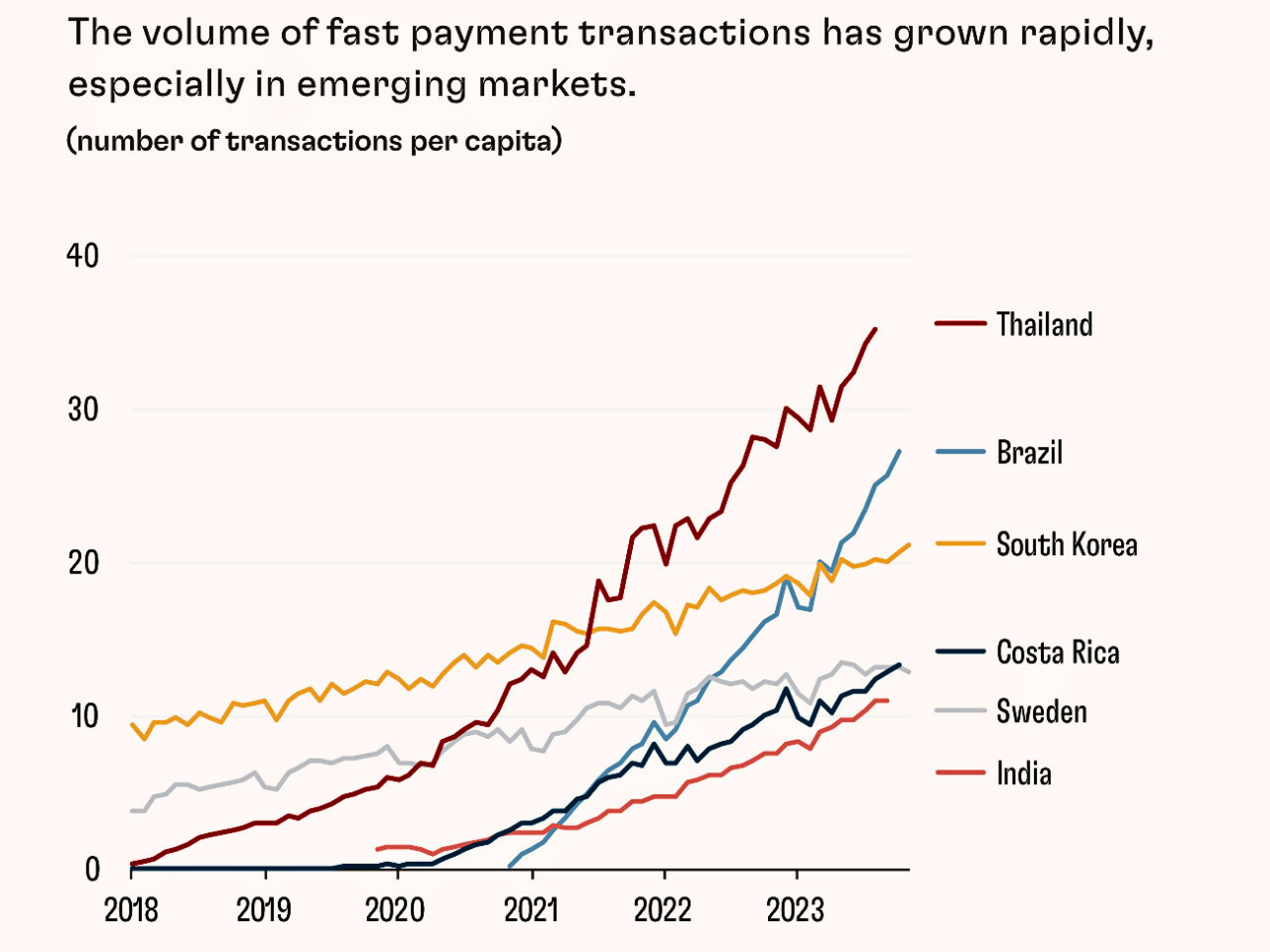

The Future of Finance: How Fintech and Public-Private Partnerships Are Revolutionizing Payments, Credit, and Investment

Brazil's Pix was launched in 2020 by the central bank and has just recently reached over 90 percent of the adult population using it regularly for their everyday purchases. India's Unified Payments Interface (UPI) is a single platform connecting banks, fintechs, and tech firms with the oversight of the central bank. In the United States, Venmo and Zelle still remain largely incompatible. In China, Alipay and WeChat Pay were initially both stand-alone platforms. In Peru, similar to China, having Yape and Plin as competing systems caused comparable challenges.

Food Safety: The Key to Unlocking Africa's Agricultural Potential and Economic Growth

which has generated $600 million in additional investment and $700 million in additional sales. This has been done with Government of Canada funding through the Facility for Resilient Food Systems (FRFS), which supports food safety as well as food loss, waste reduction, and food supply chain efficiencies

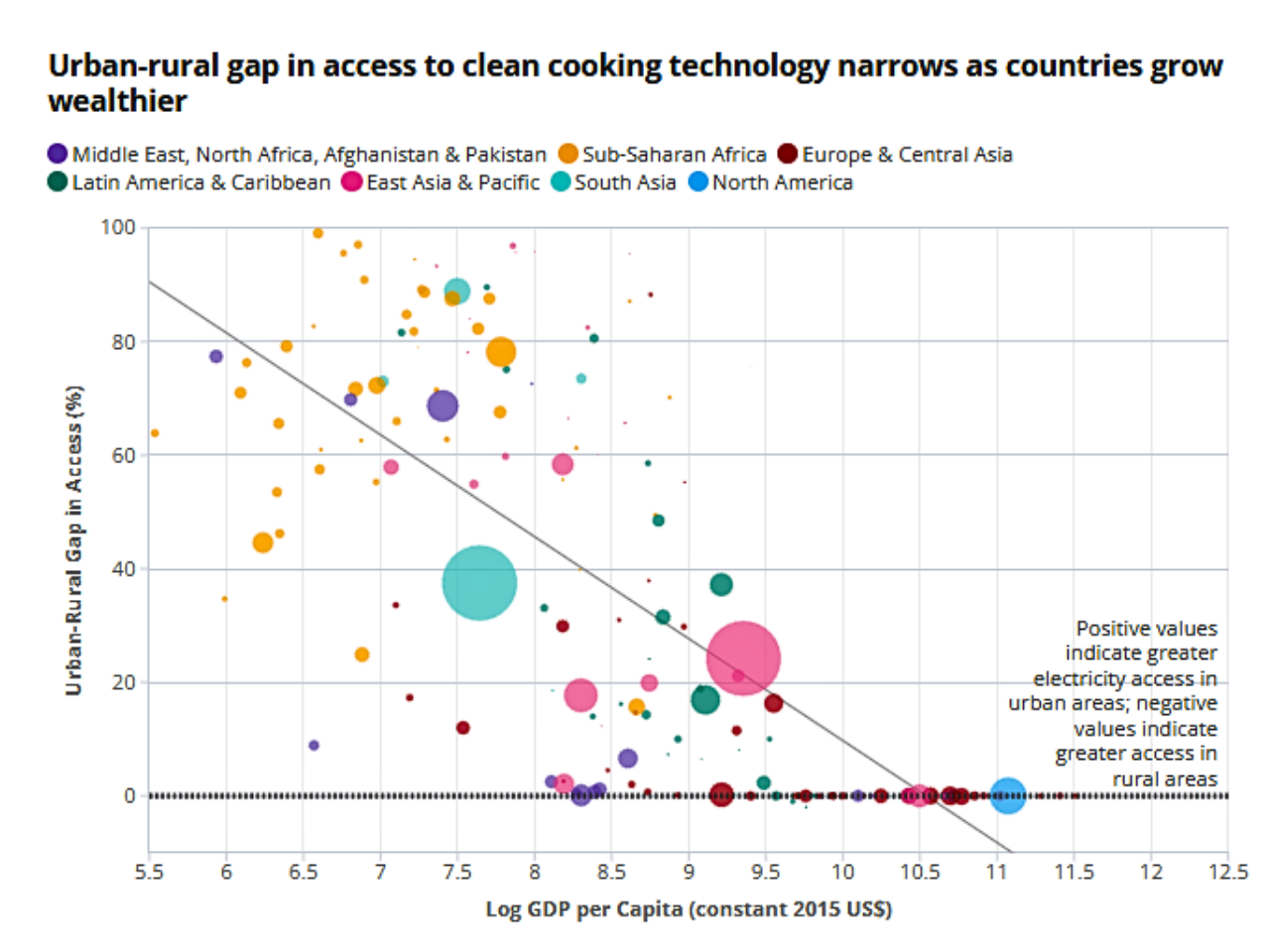

Rural Areas Left Behind: 44% of World Lives Without Access to Basic Necessities

Over the last sixty years, the world has encountered dramatic demographic change. Since 1960, the percentage of people living in rural areas has steadily declined due to the expansion of cities and the overall advance and speed of urbanization globally. In 2008, the majority of the world lived in rural areas while they maintained their lives, but without warning, worldwide populated urban areas dramatically increased their majority share

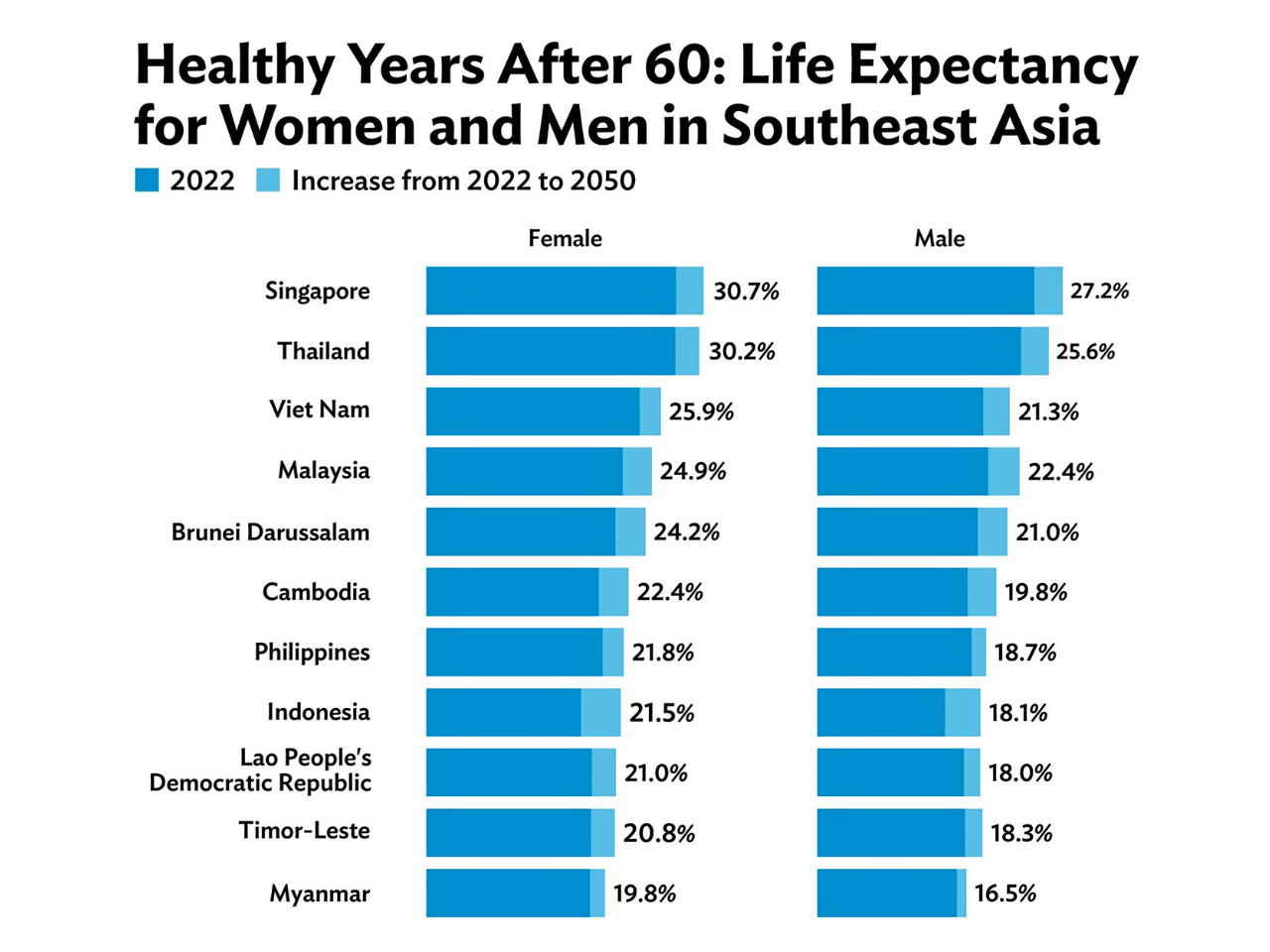

Philippines' Aging Population Set to Double by 2050: Can the Country Keep Pace?

The Philippines is in demand for a demographic change that will reopen the priorities of its economy, society, and public policy. The number of old Filipinos is expected to double by the year 2050, which creates pressure on the nation’s health care systems, elderly care services, and pension schemes

Climate Change Threatens Global Health & Poverty: Urgent Action Needed

Climate issues such as heat stress, diarrhea, malaria, and hunger can cause 250,000 deaths a year between 2030 and 2050, which challenges an important frame of adaptation. The fee, including only health systems and other areas such as agriculture and hygiene, is expected to reach USD $2 to 4 billion annually by 2030. The countries most at risk will be those that are developing countries, as they will have further weakened health systems

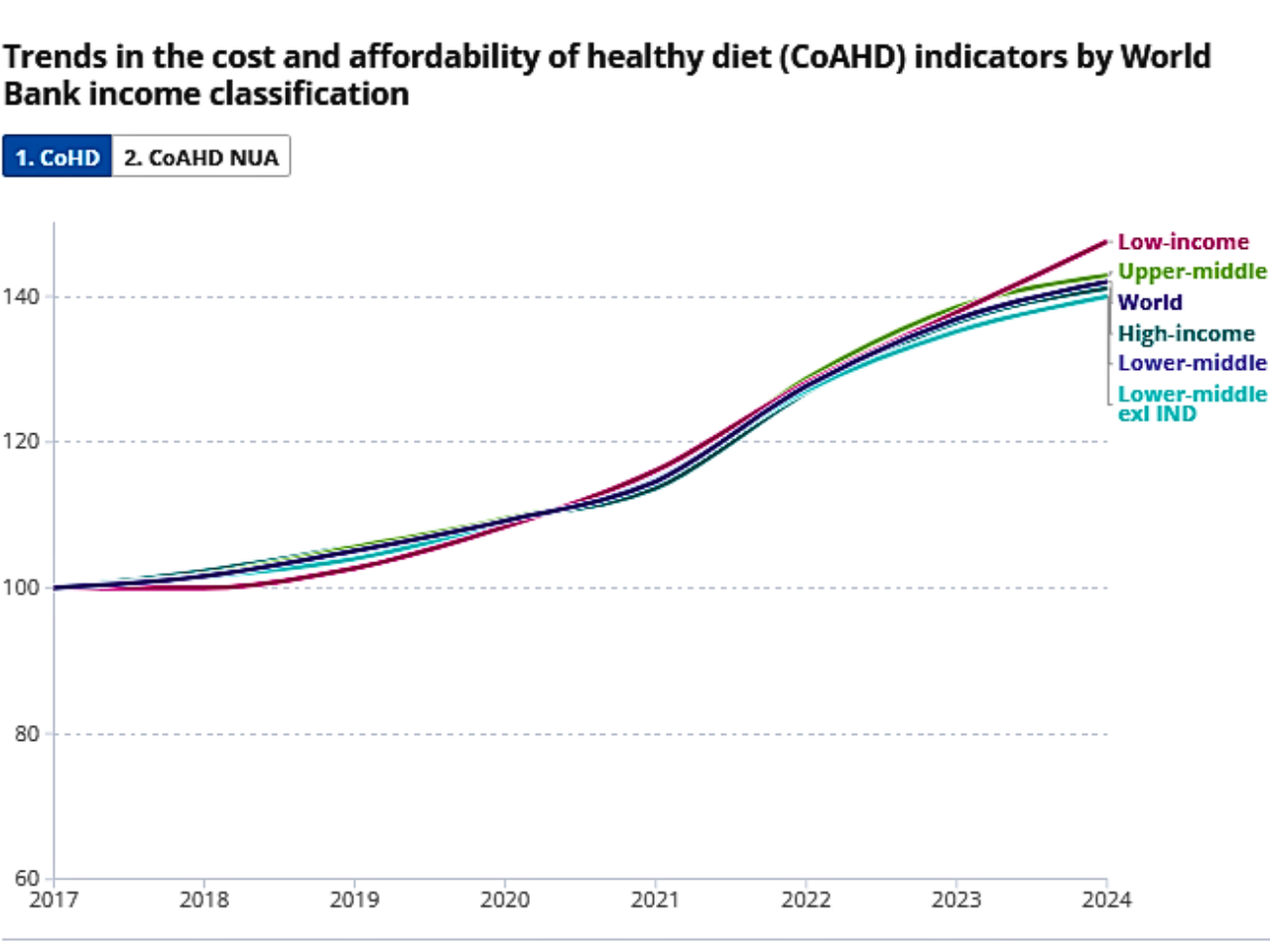

The Rising Cost of Nutrition: Can everyone afford a healthy diet?

The (SOFI) report of 2025 says that low-income nations, especially those in Sub-Saharan Africa, need to become a global movement towards more affordable, healthy diets. Based on the report, even if the global average price of a healthy meal increases to $4.46 per individual per day in 2024, only 48.8 million fewer individuals would still not be in a position to afford it, leaving close to 2.6 billion individuals in poverty