The Future of Finance: How Fintech and Public-Private Partnerships Are Revolutionizing Payments, Credit, and Investment

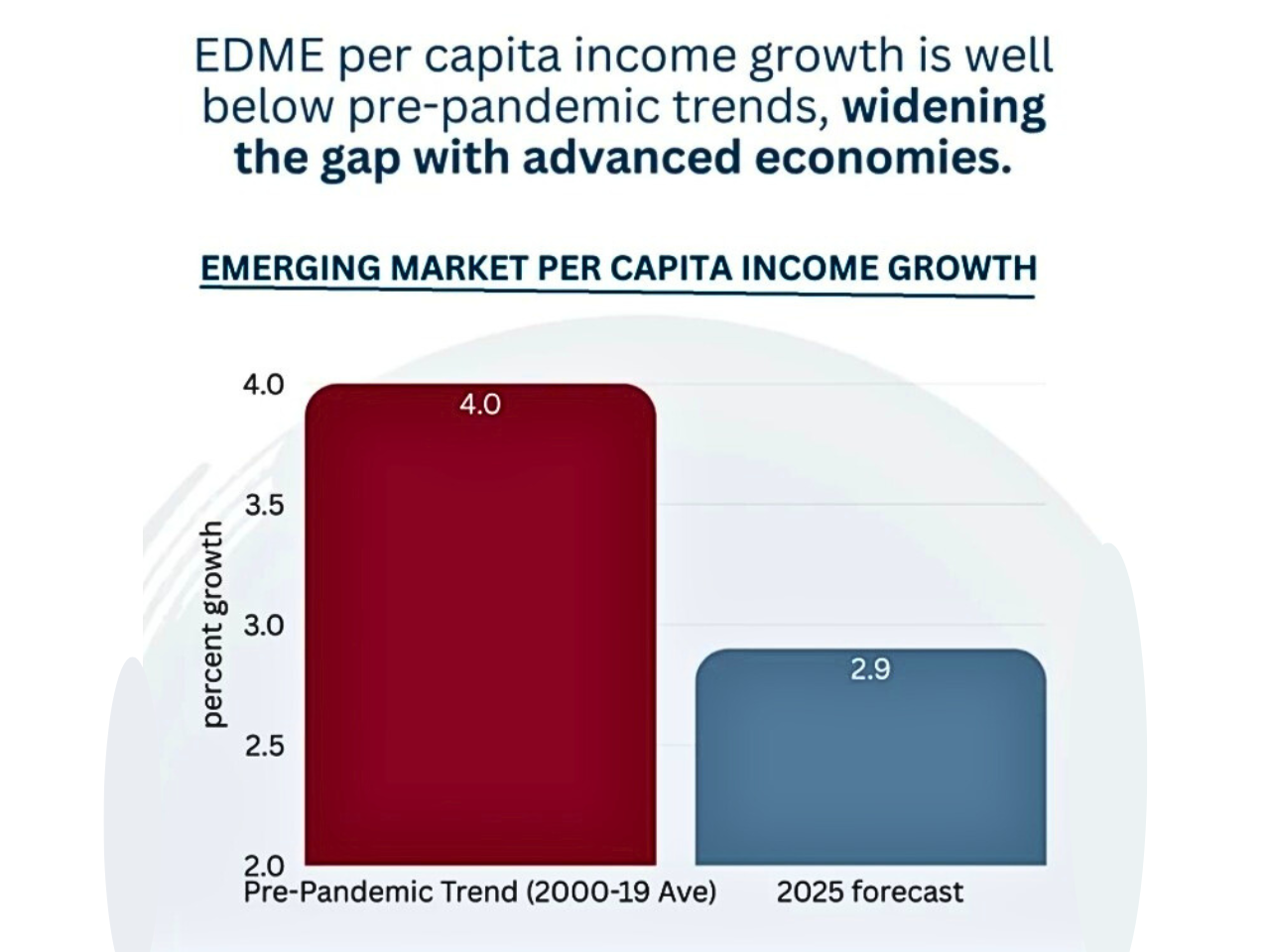

The financial services industry has been experiencing a massive revolution over the past ten years due largely to digital disruption. Financial technology firms, multinational technology companies, cryptocurrencies, and artificial intelligence technologies have made their marks on how people move, borrow, and invest money. Digital innovation often starts with a new concept, whether that is a new method of processing information, a business model that breaks convention in delivery, or a financial service that takes a different form. However, ideas alone are not enough. They require investment, infrastructure, and eventual scale to achieve impact. In finance, innovation can be even more disruptive. Startups have developed nimble financial products, tech giants have claimed the payments and lending industries as their own, crypto assets and stablecoins have offered solutions to traditional currencies, and AI is being utilized in service delivery. Each of these has exerted pressures on banks, insurers, and asset managers to adapt. It should be noted that new technologies tend not merely to be substitutes. Though they may disrupt incumbents initially, they tend to evolve into complements enhancing accessibility, driving competition, and diversifying the financial system. By all means, innovation also comes with risks: without governance arrangements, it will result in instability or exclusion. Payments can be viewed as the building blocks of financial inclusion, because payments often provide access to savings, lending, or insurance.

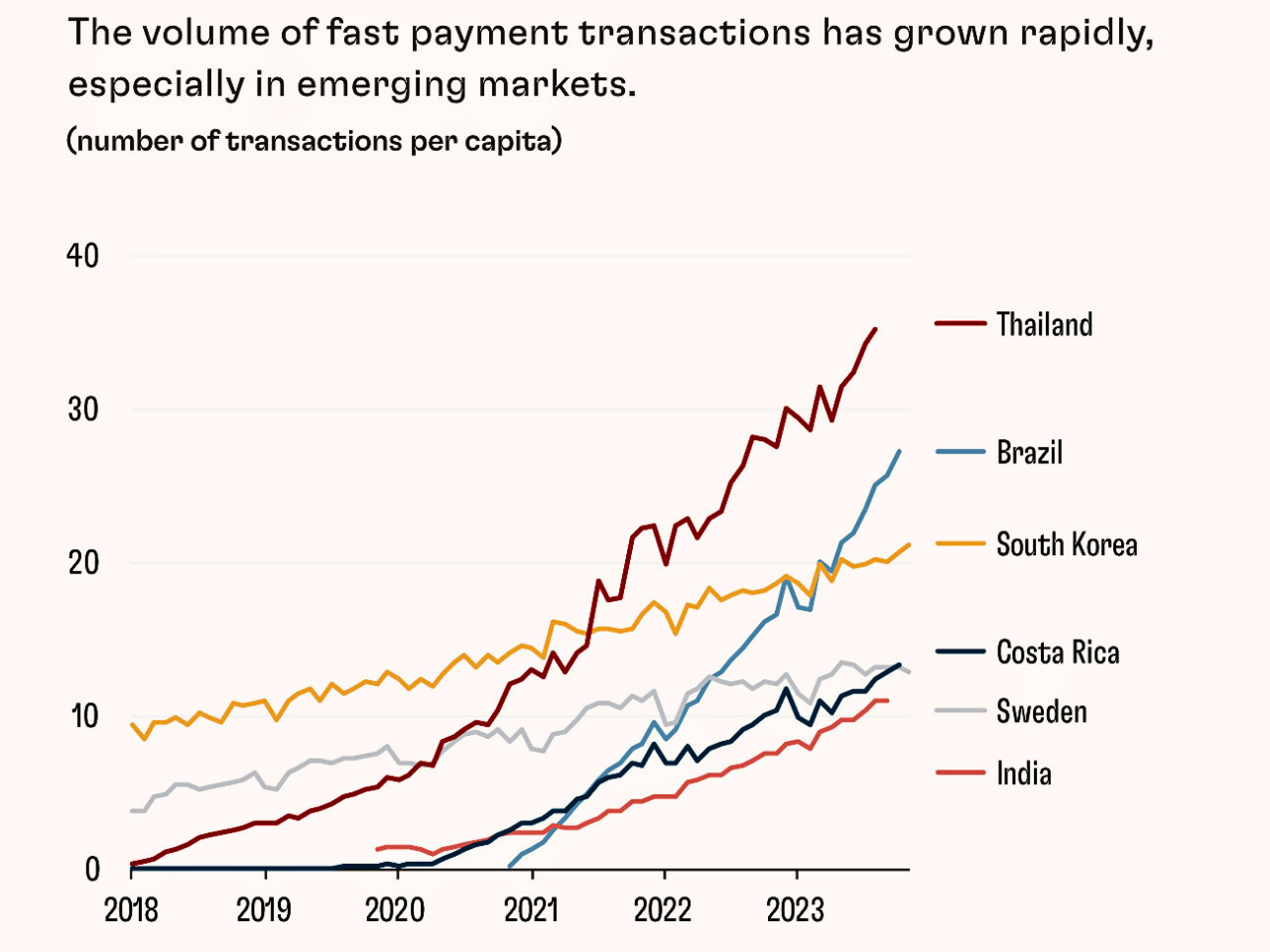

Payments were the first opportunity many fintech and tech companies pursued in finance before examining other products. In the last decade, the advent of real-time, or "fast," payment systems has changed the way people make payments, particularly in developing regions of the world. Often it is envisioned that instant systems would be built on and operated by fintechs and then, in some cases, traditional banks, but the most successful initiatives have often included even more substantial public-sector involvement in some capacity. Brazil's Pix was launched in 2020 by the central bank and has just recently reached over 90 percent of the adult population using it regularly for their everyday purchases. India's Unified Payments Interface (UPI) is a single platform connecting banks, fintechs, and tech firms with the oversight of the central bank. Thailand's Prompt Pay and Costa Rica's SINPE Móvil also fit the public-sector-centric models.

In contrast, markets that rely on private systems often face fragmentation. In the United States, Venmo and Zelle still remain largely incompatible. In China, Alipay and WeChat Pay were initially both stand-alone platforms. In Peru, similar to China, having Yape and Plin as competing systems caused comparable challenges. In such instances, policymakers intervened to provide interoperability. Generally, competition between fintechs, big techs, and banks has been fruitful, with participants getting quicker, cheaper, and more stable services, while policymakers aimed to provide for inclusion and resiliency in the overall system. Credit is a prerequisite for both business and household sectors, and fintech innovation has transformed its supply. In the first wave of digital innovations, peer-to-peer lending and other fintech platform alternatives to banks appeared destined to succeed by providing faster approvals and using alternative data to deliver credit scores. However, the landscape began shifting when large technology companies entered lending. Amazon in the United States and Alibaba in China have developed merchant credit programs, while other platforms like Mercado Pago in Argentina targeted small businesses ignored by banks. These developments and innovations have filled financial gaps.

Free Membership Register

In China, for example, technology-based lending has been less dependent on real estate collateral than bank-based loans. In the USA, fintech lenders have often delivered credit to small businesses in struggling regions. Such efforts have opened some access to capital, but the scale and impact have varied by country. At the same time banks have evolved too, changing their business models, integrating alternative data sources, and becoming platforms. Some challengers have emerged as licensed banks themselves, including Revolut in the UK and Nubank in Brazil. What was initially a competitive rivalry has morphed into coexistence with mutual adaptation. While fintechs and big techs borrow from established services, crypto assets and decentralized finance (DeFi) construct alternative financial systems. Crypto assets were designed to eliminate reliance on institutions, but they were popularized primarily as speculative assets and a little political power in particular countries. Even with the rhetoric of decentralization, the crypto markets are still intermediated, with platforms and exchanges dominating. Unbacked crypto-assets are extremely volatile and generally lack practical use. Stablecoins emerged with the goal of offering more stability, pegged to fiat currencies such as the US dollar. Generally backed by traditional assets, such as Treasury securities, stablecoins come with their own risks, such as fraud, illegal financial flows, and threats to monetary sovereignty. Over 98 percent of the value of stablecoins has been closely linked to the dollar, and given their scale of global usage, the implications for weakening of domestic currencies in other jurisdictions could be significant. Nonetheless, the trends reflected by crypto and DeFi demonstrate the potential opportunities in financing for the future. Tokenization and programmable money, coupled with the use of tokenized systems (like in cross-border payments), could potentially unite messaging, settlement, and asset transfer into a single step, increasing efficiencies for finance. Innovative capabilities in capital markets may also result from atomic settlement and enriched collateral management. Developments of this type foreshadow a hybrid situation where central banks remain the primary institution and private innovation brings new capabilities. The greatest financial innovation success stories, such as UPI in India and Pix in Brazil, have come about as a result of public-private partnerships.

There are also heightened risks; major failures in crypto could have knock-on effects in mainstream finance that reach into global markets. This indicates the need for preemptive regulation to capture innovation without destabilizing the financial system. One recent effort, Project Agorá, unites commercial banks and central banks to examine how tokenization and combined ledgers might enhance cross-border payments. The last ten years have demonstrated how radical concepts can ultimately turn into revolutionary innovations in payments, credit, and investment. FinTechs and big techs that at once appeared to threaten banks are now coexisting and even augmenting banks. Meanwhile, crypto and DeFi continue to experiment with radically different financial models. In circumstances where public authorities have taken a more interventionist role, as in India and Brazil, it is possible to reach financial inclusion and efficient financial services. In instances where systems are not integrated, often this necessitates some type of policy intervention.

The debate is not if fintech can revitalize economies, but how that revitalization is attainable. With progressive policy, resilient infrastructure, and effective public-private partnerships, fintech advancements can be focused on inclusion and stability. Without having this fragmentation, non-inclusion, and inherent risk, financial prospect is under control. The tradeoff between disruption and cooperation in defining the financial systems of the future will be central to it.

Latest Explained

Food Safety: The Key to Unlocking Africa's Agricultural Potential and Economic Growth

which has generated $600 million in additional investment and $700 million in additional sales. This has been done with Government of Canada funding through the Facility for Resilient Food Systems (FRFS), which supports food safety as well as food loss, waste reduction, and food supply chain efficiencies

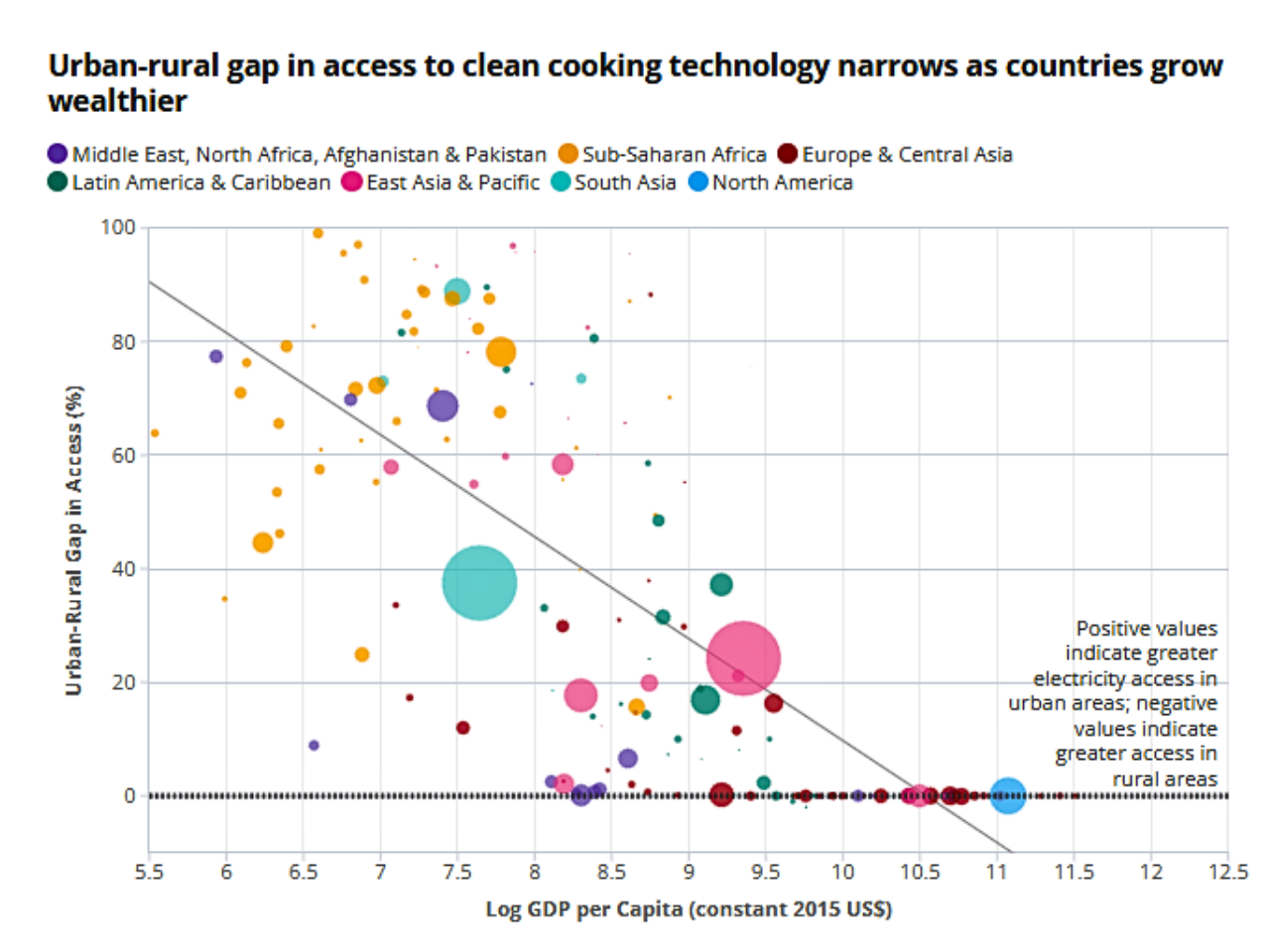

Rural Areas Left Behind: 44% of World Lives Without Access to Basic Necessities

Over the last sixty years, the world has encountered dramatic demographic change. Since 1960, the percentage of people living in rural areas has steadily declined due to the expansion of cities and the overall advance and speed of urbanization globally. In 2008, the majority of the world lived in rural areas while they maintained their lives, but without warning, worldwide populated urban areas dramatically increased their majority share

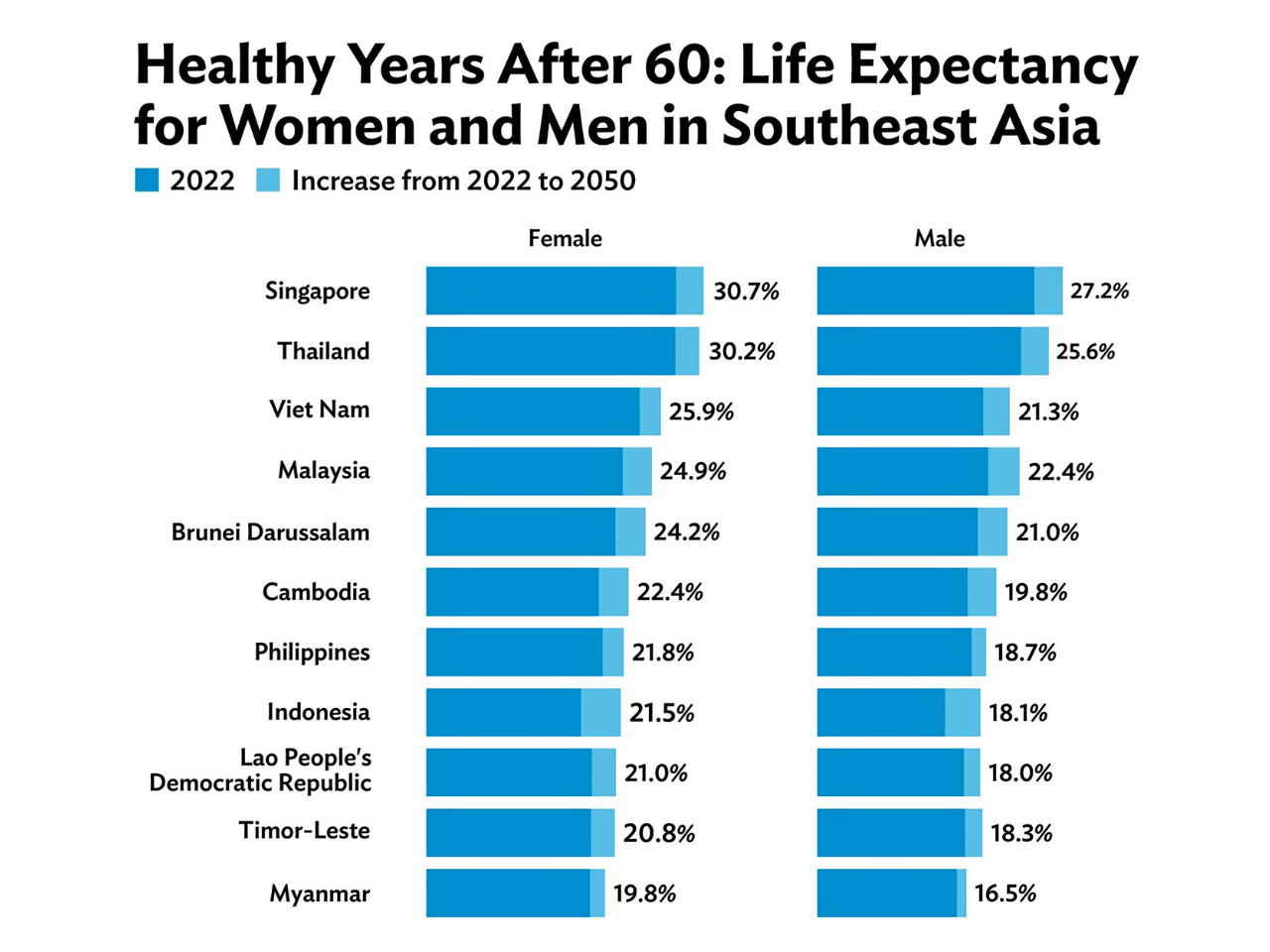

Philippines' Aging Population Set to Double by 2050: Can the Country Keep Pace?

The Philippines is in demand for a demographic change that will reopen the priorities of its economy, society, and public policy. The number of old Filipinos is expected to double by the year 2050, which creates pressure on the nation’s health care systems, elderly care services, and pension schemes

Climate Change Threatens Global Health & Poverty: Urgent Action Needed

Climate issues such as heat stress, diarrhea, malaria, and hunger can cause 250,000 deaths a year between 2030 and 2050, which challenges an important frame of adaptation. The fee, including only health systems and other areas such as agriculture and hygiene, is expected to reach USD $2 to 4 billion annually by 2030. The countries most at risk will be those that are developing countries, as they will have further weakened health systems

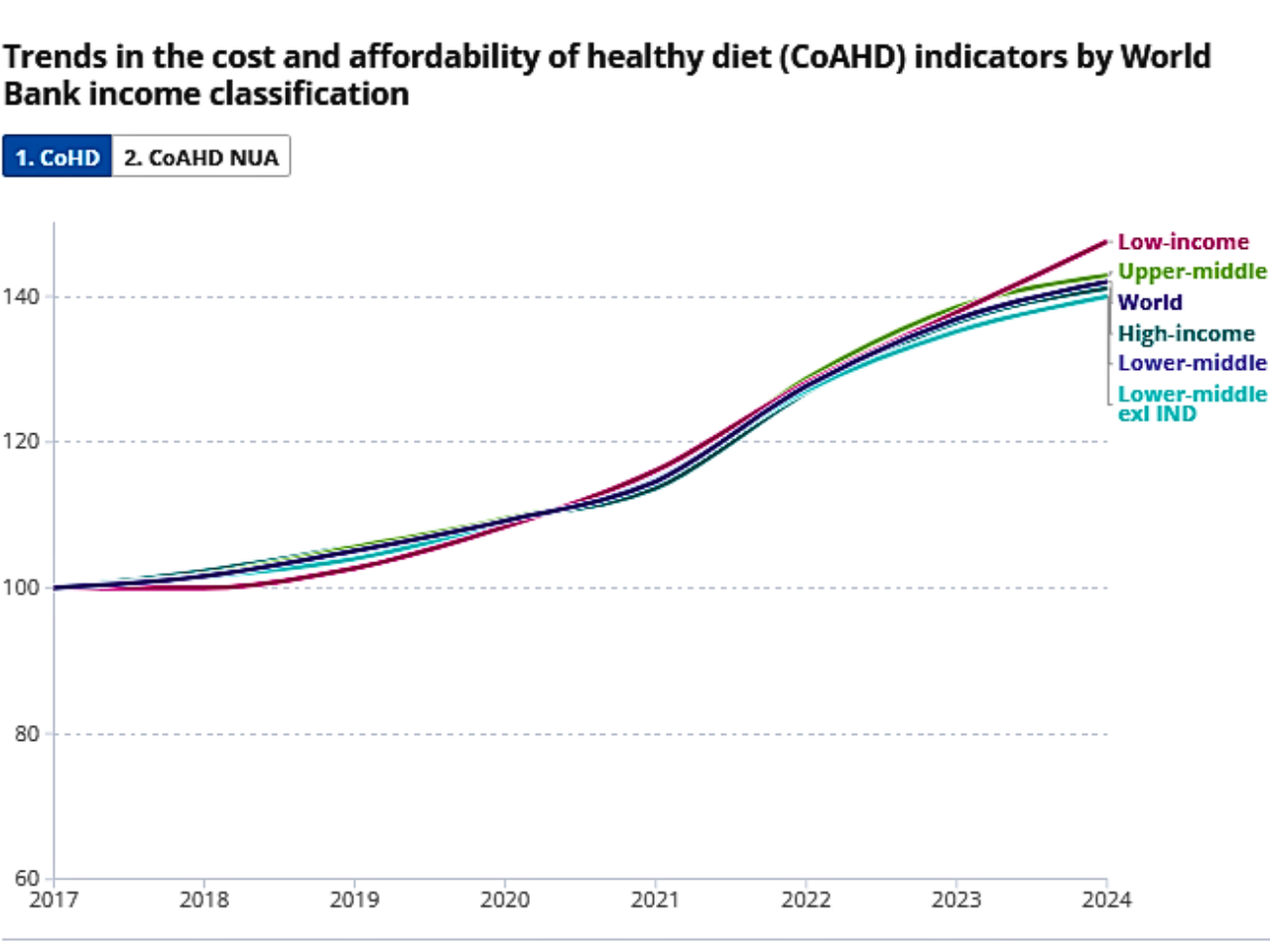

The Rising Cost of Nutrition: Can everyone afford a healthy diet?

The (SOFI) report of 2025 says that low-income nations, especially those in Sub-Saharan Africa, need to become a global movement towards more affordable, healthy diets. Based on the report, even if the global average price of a healthy meal increases to $4.46 per individual per day in 2024, only 48.8 million fewer individuals would still not be in a position to afford it, leaving close to 2.6 billion individuals in poverty

Blended Finance: Bridging Fragmented Aid and Development Needs

The International Development Association (IDA), sees more than 90% of its financing go through national budgets and gets each donor dollar to translate into $3 to $4 in tangible results, representing the importance of scale and management

Economy growing fast, but youth employment isn't keeping up

Youth unemployment remains high across many pats of Asia and the Pacific unemployment rates, 2025. Young people are willing and able to work but do not get jobs; they face many struggles and obstacles in the world