Climate Change Threatens Global Health & Poverty: Urgent Action Needed

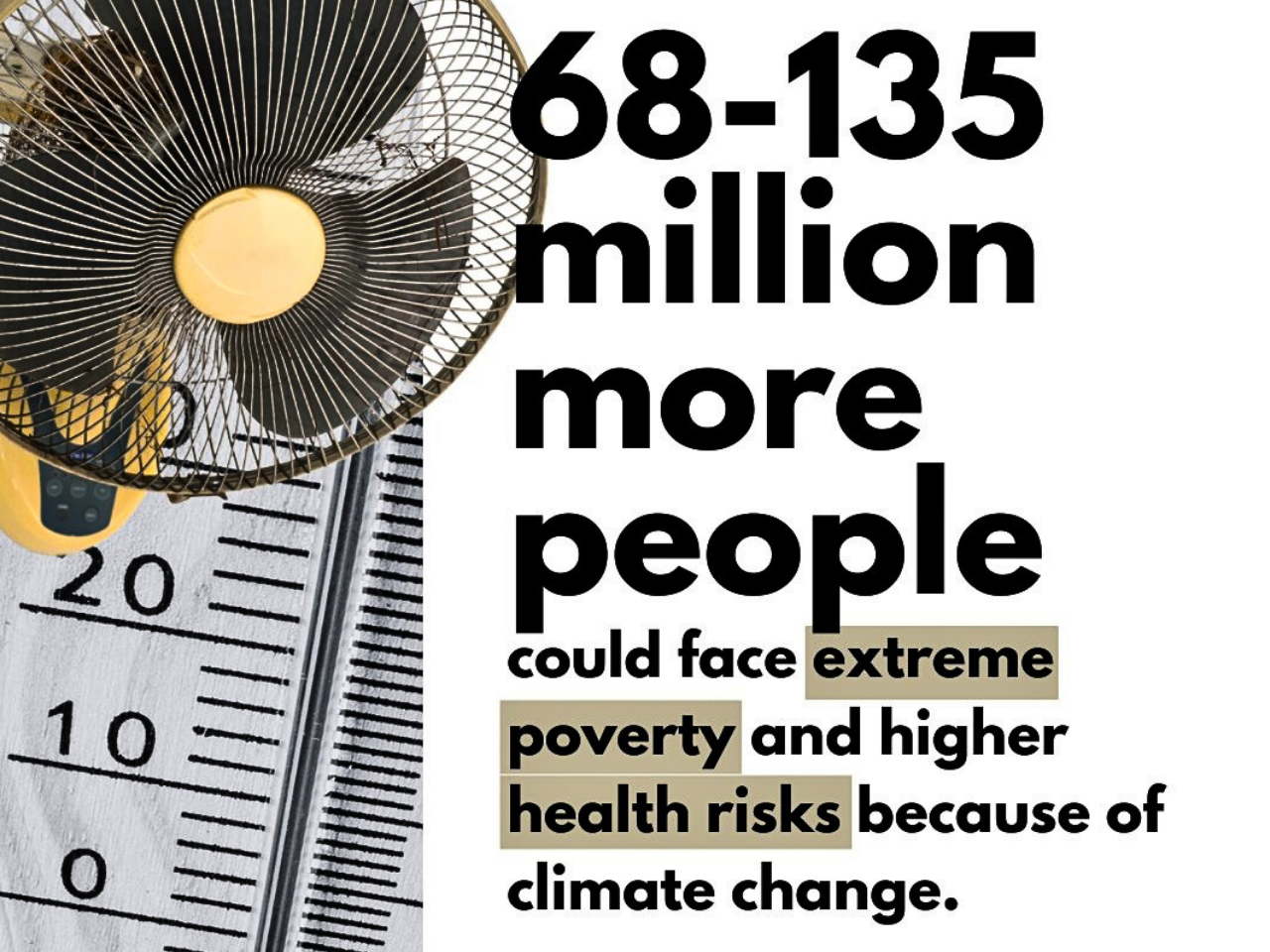

Climate change increases poverty and health risks as a strong threat multiplier. Climate change affects health, and climate change impacts are already harming global health, and in 2030, climate impacts could push 40 million people into extreme poverty. Unprecedented pressure is already on overstretched health systems, and the cost of inaction would be too high for the people and planet. The World Bank has set a specific climate and health track for the overall climate agenda. The goal is to help health systems become more resilient to the increasing effects of climate change by providing agriculture with logical solutions and targeted expenditures. Extreme rainfall and an increase in natural calamities are two ways that climate change leads to global health risks, leaving 3.6 billion people in risk-prone areas.

If nothing is done immediately, weak health systems are at risk of collapse. Climate issues such as heat stress, diarrhea, malaria, and hunger can cause 250,000 deaths a year between 2030 and 2050, which challenges an important frame of adaptation. The fee, including only health systems and other areas such as agriculture and hygiene, is expected to reach USD $2 to 4 billion annually by 2030. The countries most at risk will be those that are developing countries, as they will have further weakened health systems. We can improve global population health by reducing greenhouse gas emissions and developing a durable system for transportation, energy, and food. The World Health Organization (WHO) reports that 2 billion people do not have safe drinking water, and 600 million people suffer from annual food-borne diseases; young children are inconsistently affected. Health shocks driven by climate change affect those who are underinsured and at risk.

In its climate strategy, WHO has three targets to inform climate action to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and ensure healthy ideas. To adapt to climate change and maintain healthcare systems through universal health coverage (UHC) and low-emission provisions of care and to protect the population through vulnerable assessment, increase monitoring, and support adaptation in sensitive domains, such as health financing, agriculture, and water resources. In fact, in 2023 alone, more than 20 million people were displaced due to climate change effects; By 2050, this number will reach 216 million. Climate change affects the functioning of health systems due to increased vulnerability, which means displacement, food insecurity, and the risk of exposure to disease in our patients. There is cause for concern; in light of climate change’s potential to worsen food and nutritional inadequacy, increase exposure to infectious disease at scale within already strained systems, and increase risk, such as displacement with over 20 million people displaced in 2023 and an expected 216 million by 2050, healthcare systems must manage both short-term vulnerability and long-term effects of climate change in these precarious contexts (the Double Exposure vulnerability context), especially in resource-limited settings.

Free Membership Register

Climate change has many impacts on healthcare and ranges from compromising access to healthcare services, harm to infrastructure and ecosystems, risks of population health exposure, and direct exposure risks to the physical and mental health of healthcare workers. The vulnerability of healthcare organizations to climate change means they must work to limit their reliance on the infrastructure of the healthcare system. That said, healthcare organizations also contribute to climate change with greenhouse gas emissions. Evidence-based policies that consider these issues can help organizations and policymakers to identify ways in which they can take the carbon out of the system. Not only does poor health directly or indirectly burden the individual, but the community and the economy also hold it back by losing out on growth or limiting or declining opportunities for education, work, or participation in society in a multitude of ways. Undoubtedly, chronic diseases result in wasted productivity, costing U.S. employers billions of dollars each year. It is well established that levels of education are significantly associated with higher quality of health and mortality. Every year, 1.8 million children's lives would be saved if wealth-related inequality in low- and middle-income nations were addressed.

Even small investments, such as 0.1% of GDP in social security, labor, housing, and community policies, can lead to heavy health benefits, benefiting 150,000 people in a population in a very short time, that is, four years. But health inequalities cannot be resolved in isolation; widening economic inequality, mixed with structural discrimination, conflict, and climate disintegration, remains a serious obstacle to health equity. Income inequality between countries is dire. But the inequality within the country has nearly doubled in the last 20 years and now exceeds inequality between countries. In 201 countries, the top 10% take in 15 times more than the bottom half of the population. Weak tax systems mean billions continue to be cut off from universal services, and 3.8 billion people are not offered adequate social protection, such as a child benefit or paid sick leave. And on top of this, persistent gender and racial discrimination undermine opportunities, and 2.4 billion women of working age are cut out of the economy.

The poorest countries are also experiencing rapidly growing loans, whose interest payments have increased by 4 times in 10 years, which limits the amount of money available to invest in health and social development. Climate change is affecting poor people who depend on natural resources, as women and girls are particularly affected in collecting water and fuel. Forced displacement of people since 2008 has tripled to a total of 122 million people, which continues to produce health inequality that removes services, support, and stability. Finally, the WHO recognizes the need for strong governance and decentralized resource allocation for local municipalities and enables people and communities to embrace policies and decisions that embed equity as a priority in their work and services. A socio-economic shield is usually present in health; those who are less educated, poor, and more deprived are less likely to reduce health and reduce it soon. By ensuring that everyone has an equal chance to live a respectable and healthy life free from social or economic discrimination, governance and policy procedures will enable us to realize equitable outcomes.

East Asia and Pacific: Development forecast 4.5% but decreased by slow demand from China. South Asia: forecast growth of 5.8%, making it the fastest-growing region, led by India with 6.3%. Sub-Saharan Africa: forecast growth is 3.7%, not sufficient to address population growth. Europe and Central Asia: forecast growth of 2.4%, limited by the war in Ukraine and energy costs. Latin America and the Caribbean: war-torn and mired in low investment and stagnant at 2.3%. Middle East and North Africa: forecast growth of 2.7%, continued support from oil, but fiscal pressures tempered growth. The World Bank has identified three important policy pillars to gain momentum. It is important for sustainable development to revive target investment in infrastructure, digitization, and climate-flexibility expenses. In developing economies, fiscal space authorities should rebuild revenue, reduce the dependence on subsidy, and support subsidy to support social and development programs. The international community should also be prepared to assist delicate and conflict-affected states. Global Economic Prospects (June 2025) clarifies that the drivers of global development (trade, investment, and financial stability) are severely weak. In the absence of bold action, developing economies are at risk of suffering from dull growth and inverted "lost decades." Nevertheless, there is also a reason for optimism. With infrastructure and investment in people, sound fiscal policy, and renewal by global cooperation, economies can successfully navigate these turbulent times. The options made in the coming year will determine whether the next decade will be characterized by a renewed opportunity for inequality or collective flexibility and development.