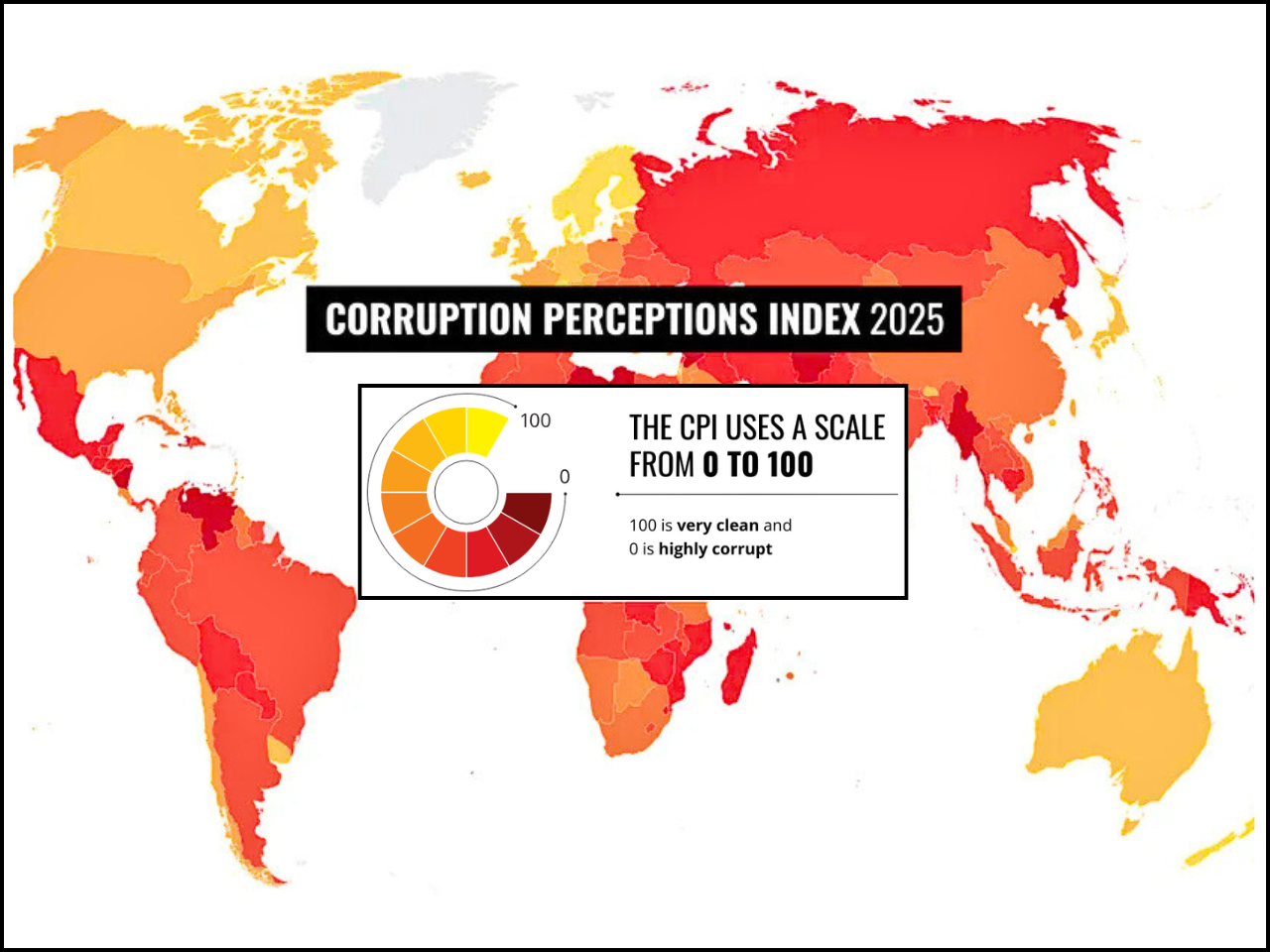

Global Corruption Hits Decade-Low: CPI 2025 Report Sounds Alarm on Governance

The publication of the Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) 2025 marks a turning point in discussions of governance, accountability, and political integrity worldwide. The report, which Transparency International publishes, assesses the perceptions of citizens, experts, and business people regarding the perception of the quality of governance through a 182-country and territory outlook on the perception of corruption in the public sector, and provides one of the most influential snapshots of the quality of governance in the world.

The findings of this year portend a disturbing turnaround. It has dropped to its lowest point in over 10 years, and this is a cause of increasing concern that the progress made in anti-corruption is now stagnant or actually reversing in several regions. According to the report, corruption perception in the global context is taking a different form due to political instability, deteriorating democratic protection, and declining freedom of the citizens.

The CPI is a perceived corruption index in the institutions of the state on a scale of between 0 and 100, with 0 representing a highly corrupt institution and 100 representing a very clean institution. The index is a composite of expert ratings and business surveys as opposed to actual measurement of corruption and is based on 13 independent data sources. The average in the globe in 2025 was 42, which demonstrates that not all governments can avoid misusing the power of the people. Over two-thirds of the nations had a score of below 50, meaning they were facing serious corruption issues in huge portions of the world. Nordic and highly institutionalized democracies still dominate at the top of the index. Denmark was ranked first with a score of 89, and this has followed a long track of good performance in governance. Other advanced nations are Finland, Singapore, and New Zealand, which are known to have a good reputation in terms of good institutions and open administration.

On the other extreme, the least scored are conflict-affected and politically unstable states. There were the lowest scores in such countries as Somalia and South Sudan, where institutions are weak, and the crises of governance continue. The statistics emphasize that corruption tends to go systemic in the environment where the oversight systems are ineffective, or there are no systems. The most important lesson of the CPI 2025 is the apparent correlation between corruption control and democratic governance. The total score of countries that were classified as full democracies was 71, as compared to the 32 in authoritarian regimes. The report argues that corruption can be precluded through independent courts, active civic participation, and free media. In a system where these checks and balances are weak, the chances of corruption are high. This trend is becoming even more apparent in traditionally powerful democracies, some of which experienced decreasing scores in recent years. Interestingly, there was a significant decline in some of the high-income democracies such as the United States, Canada, and even some parts of Europe. Analysts indicate that these trends might be caused by political polarization, decreased watchfulness, and increasing worries about lobbying and campaign funding. The results of the CPI show that corruption does not arise in a vacuum; it thrives in situations where civic space is reduced. Those countries in which the freedom of expression, association, and journalism is limited are likely to be ranked low. The report says that close to two-thirds of countries that have deteriorated scores since 2012 also recorded diminished civic liberties. The report mentions the importance of journalists and civil society organizations in the process of uncovering misconduct. However, in several areas, the investigators of corruption are intimidated, pressured by the law, or even shot down. These circumstances lead to less transparency and enable the misdeeds to go unmonitored. One of the significant changes discussed in the report is the increase in the number of youth-led protests in 2025. In many countries that had low CPI scores, young citizens came out to insist on accountability, good governance, and delivery of good services to people. The movements illustrate how corruption is increasingly influencing the level of trust and political legitimacy of the people.

In other instances, the long-term demonstrations on the side of the people helped bring about change in the political system, which showed the strong relationship between the perception of corruption and the general level of dissatisfaction in the society. Corruption is now being equated by people with financial malpractice and inequality, poor services, and the absence of economic opportunities. Besides politics, the daily impacts of corruption are also revealed by the CPI 2025. Mismanagement or diversion of public funds negatively affects the basic amenities such as health, education, and infrastructure. This unequal distribution in favor of the less-fortunate neighborhoods contributes to inequality and decreased social mobility. Another point that is highlighted in the report is transparency in the finances of the people. The lack of proper supervision may result in fiscal crisis, higher debts of the population, and less ability to handle events like climate change or economic shocks. The most important thing in the analysis of this year is that corruption is an international phenomenon. The illicit funds are transferred across nations by means of money laundering, corporate bribery, and offshore financial systems. Even those countries that have comparatively high scores can contribute to corruption unwillingly by being a destination of stolen funds.

The report recommends that the world cooperate more to seal financial loopholes and to tighten the enforcement mechanisms. Failure by one nation to act in harmony may result in a nation with weak points. Although countries in most countries experienced a decrease, the report also brings the positive examples. Countries like Bhutan, Estonia, and South Korea are mentioned to have accrued long-term benefits through the continued reforms, the digitalization of the governmental services, and enhanced anti-corruption institutions.

Such instances show that there are no predetermined trends in corruption. A stable political will, autonomous watchdog bodies, and open governance mechanisms can be the solution to a gradual positive change. Effective institutions, citizens, and transparent governance have continued to be crucial security measures. With governments facing geopolitical tension, economic unpredictability, and rising public frustration, the CPI serves as a reminder to the world that corruption is not only a legal or political problem but rather a structural problem that defines social justice, economic stability, and democratic fortitude. The question is not only about the ranking of countries, but whether the leaders will take action on the warning signs before the faith in the institutions of the people is even lower.

Monthly Edition